The relationship we have with ourselves is arguably our most important. It is equally our longest and most constant, although it continues to change as new experiences are lived. Lyle Ashton Harris explores the relationship of the self in his solo exhibition Our First and Last Love at the Queens Museum. Including multimedia and photography from the last four decades of Harris’ career, the exhibition dives into intersecting ideas related to the Black and Queer communities.

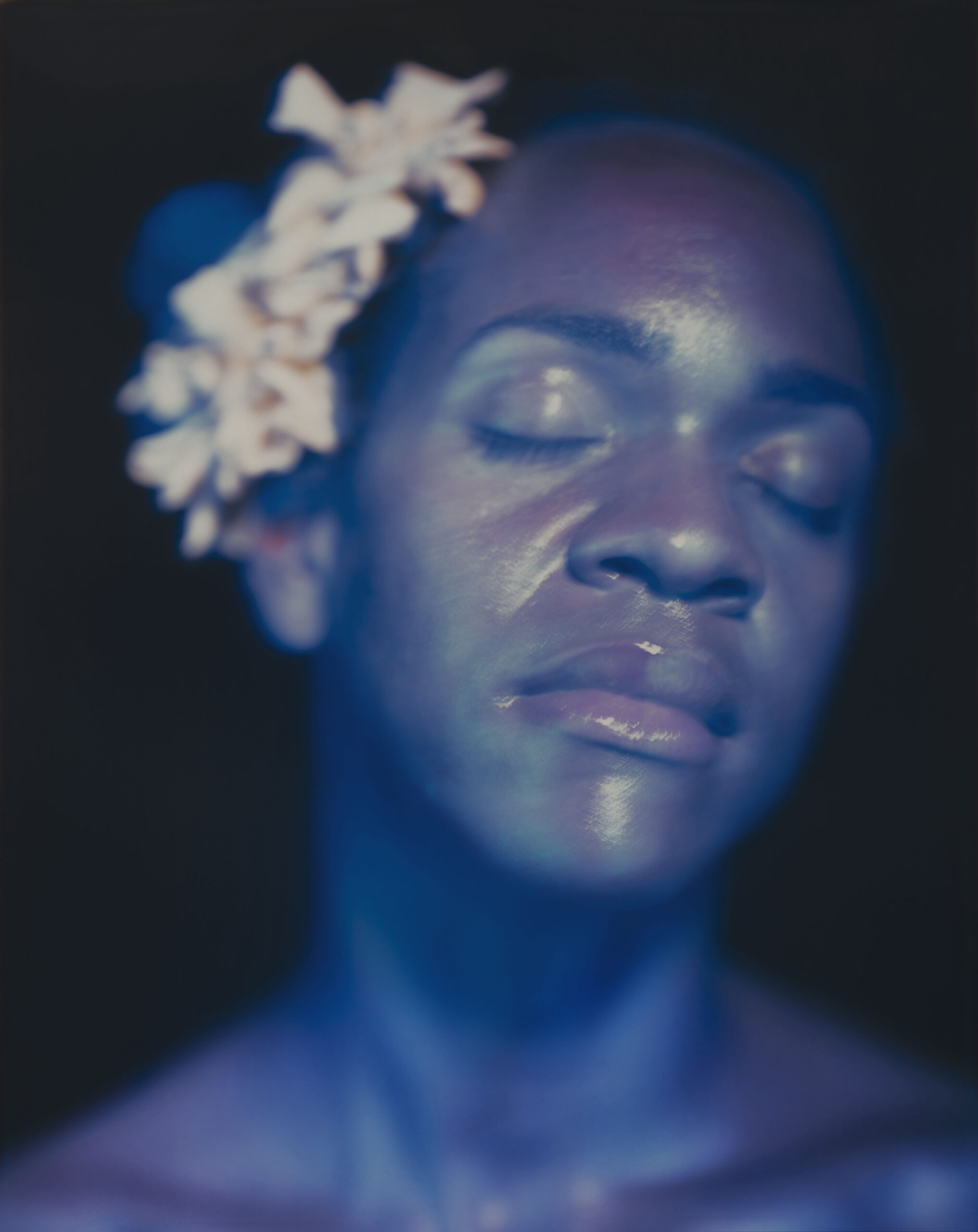

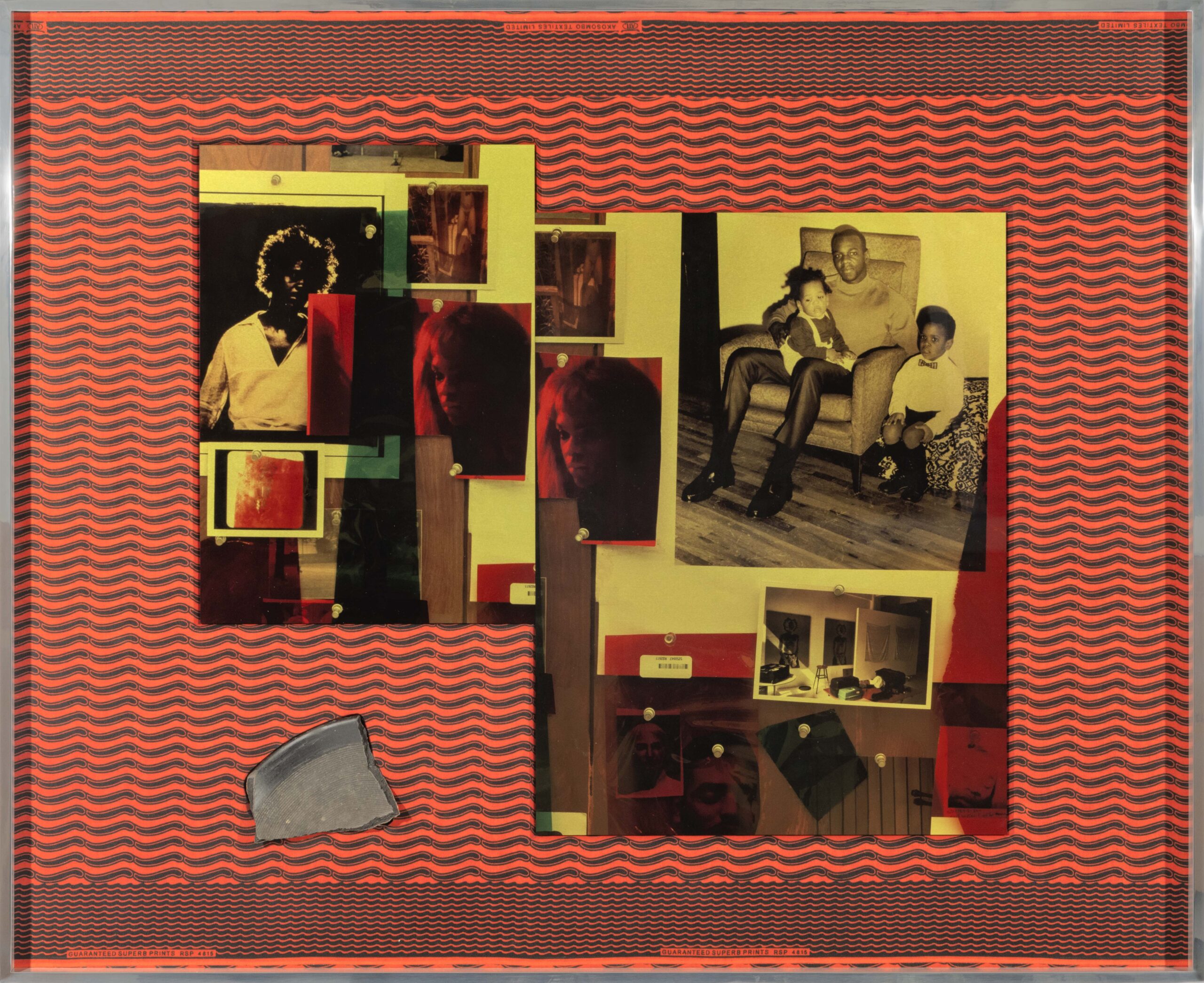

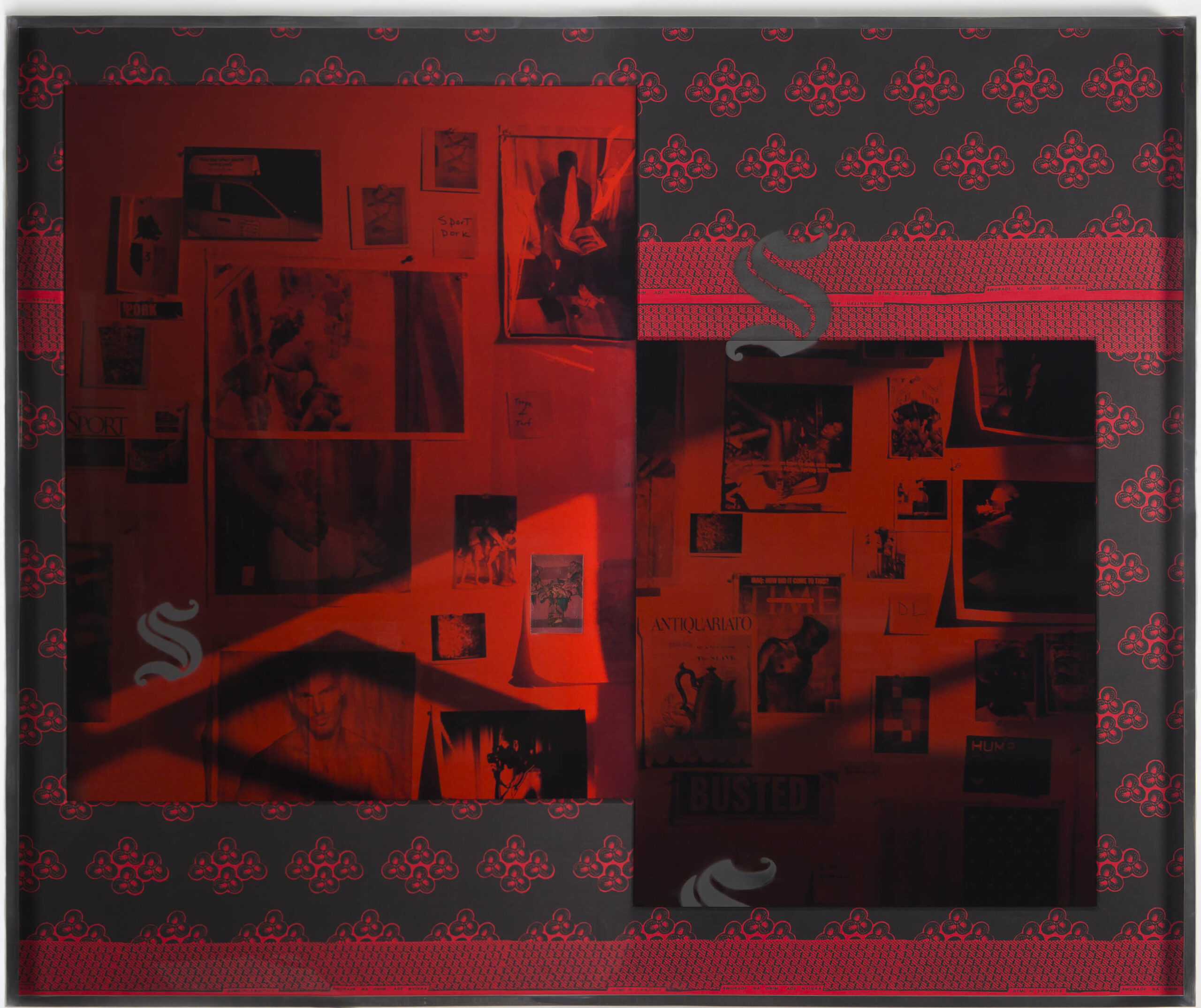

Harris’s recently completed Shadow Works guide the exhibition, as the viewer is taken on a visual journey through Harris’s youth into the artist we know today. The exhibition covers Harris’ work across mediums, showcasing various works in collage, large polaroids, video installations, vintage newspaper clippings, and textiles that the artist has been collecting and photographing since the 1980s.

Born and raised in the Bronx, with a brief moment living in Tanzania, Harris credits his youth as one of his earliest inspirations. Growing up in the 70s, the street life of New York was exceptionally vibrant and intoxicating. Harris witnessed cultural resets from the birth of hip-hop, to the fashion and art world embrace of Black artists and their culture. In his younger years Harris attended community events in Harlem, the West Indie Parade, trips to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and various Black theater trips. As he got older, he found himself intertwined with the club scene attending places like The Warehouse and various other spaces throughout the city.

From 2005 to 2012, Harris lived in Accra off and on, working as a professor for New York University’s Global Program, and during his time in Ghana, he helped jumpstart the arts program for the university. Not only did his time spent there inspire his work, it allowed him to become more immersed in various communities, as he adopted Ghanaian textiles and patterns, and incorporated them into his practice.

In his 2020 piece, Migration Times, which incorporates yellow and blue Ghanaian cloth, Harris embedded photographs that were directly printed onto aluminum, placing them onto the fabric. The shadow work within these collages uses Harris’s personal archive of photographs and puts them directly at the forefront of the piece, literally screen-printing them onto the fabric.

“While I was there, I was able to acquire certain fabrics and in a lot of ways this show comes out of my time in Ghana,” he says. “The main components of this show are the assemblages that are relatively large.”

Harris recently guest edited the Fall 2023 issue of Aperture Magazine titled ‘Accra,’ which explores his time in Ghana and showcases various political portraits he took during his time living there, some of which are also included in the exhibition.

Our First and Last Love is a form of autobiography. Using his own identity as a framework, Harris opens up conversations related to race, sexuality, and gender and how these directly relate to the Black identity. In various works, a black, green, and red color scheme–the colors of the Black Liberation flag–can be seen incorporated into the background.

Although American culture has changed significantly since Harris started working as an artist, especially after the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, Black Queer relationships are still extremely complex. To be both Black and Queer is a unique experience, as both identities can be hard to navigate, particularly as an artist. Instead of shying away from these conversations, Harris brings them to the forefront of his work, examining his experience and the way it has changed as culture has shifted throughout the decades.

“I think a lot of things have shifted in terms of masculinity,” says Harris. “It’s more complex–the complexity has always been there, but we’re finally putting it at a forefront. People today are anti-establishment and bold and visionary because the system is being challenged.”

Brotherhood, Crossroads and Etcetera #2 depicts Lyle and his brother Thomas Allen Harris. In it, the two fraternal brothers are seen kissing on the mouth as Thomas holds a gun up to Lyle’s chest. Although this photo was taken 30 years ago–in 1994–the message behind the image still resonates today. “Given that we live in the culture we did, in a racist society, and also a masculine society, it is often hard for men to relate to each other in a brotherly way, and often we commit acts of violence to ourselves and others,” explains Harris on the genesis of the piece, which was taken in 1994. “In a way, that photograph was exploring the complexities of that.”

Harris now lives in upstate New York, although his studio is in Manhattan and he continues to teach at NYU. His courses explore the performative within the contemporary, looking at photography, public performance, and critical theory as students engage in interdisciplinary ideas about art and creation. Rochelle Roget, who took Harris’s course that dove into the interworking of art education this past spring, describes Harris as being a helpful point in assisting students in discovering their identity within their artistry.

“He teaches to not hold back from your practice, and to expand,” she says. “When you don’t hold back, you allow yourself to reach greater heights. When you really put your all into something and continue to learn your craft and perfect stuff, you get the best results and become a better artist.”

Our First and Last Love, is truly an ode to self. Harris is able to take the viewer on a visual journey through various phases and experiences in his life that transcend beyond the photograph. The experiences may be personal to Harris, but they transcend the artist, and time, becoming universal. “That’s the thing about art–it can resonate over the generations with different kinds of people and different races,” he says. “I guess that’s one of the reasons that I was drawn to art, even if something was made 100 years ago or 20 years ago.”

‘Lyle Ashton Harris: Our First and Last Love‘ is on view now through September 22 at the Queens Museum.